Dancing to the Data: Exploring Spotify Danceability with Linear Regression

A STA302 Project at the University of Toronto

Dancing to the Data: Exploring Spotify Danceability with Linear Regression

Danceability is one of the most fascinating—and subjective—qualities of music. Why do some songs make people want to move instantly, while others don’t, even when they share similar tempos or genres? With the growth of music streaming platforms like Spotify, we now have access to detailed audio features that allow us to explore this question using data.

This blog post summarizes a final project completed for STA302 (Methods of Data Analysis II) at the University of Toronto, where my friends and I used multiple linear regression to investigate which musical and popularity features are most strongly associated with a song’s danceability.

Project Motivation

Spotify defines danceability as a score based on musical elements such as tempo, rhythm stability, beat strength, and overall regularity. While this metric is widely used in music recommendation systems, it raises an interesting analytical question:

Is danceability driven more by musical structure or by popularity-related factors?

Using statistical modelling, this project aimed to determine which features truly matter when predicting how danceable a song is.

Data Collection

The analysis used the Top Spotify Songs 2023 dataset, sourced from Spotify’s public Web API and published on Kaggle. The dataset contains 952 unique songs, each with:

- Machine-generated audio features (e.g., danceability, valence, energy, BPM, acousticness, speechiness)

- Popularity metrics (streams, playlist counts)

- Consistent, complete measurements suitable for regression analysis

Because the data are publicly available and contain no personal information, the project posed minimal ethical risk.

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

Initial exploratory data analysis focused on:

- Assessing variable distributions and skewness

- Examining correlations between predictors

- Identifying influential observations and potential data quality issues

This step informed later modelling decisions, including transformations and predictor selection.

Methodology

To model danceability, we fit a multiple linear regression (MLR) model following a structured, statistically rigorous workflow taught in STA302 at the University of Toronto:

Predictor Selection

- Removed non-significant predictors using t-tests on regression coefficients

- Applied subset selection, comparing:

- Adjusted R²

- AIC / AICc

- BIC

- Considered forward, backward, and stepwise selection methods

- Compared nested models using partial F-tests (ANOVA)

Model Assumptions

Key linear regression assumptions—normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity—were evaluated using residual diagnostics. When violations were detected, we applied Box–Cox and log transformations, resulting in well-behaved residuals.

Here’s the Rmd file with our code.

Results

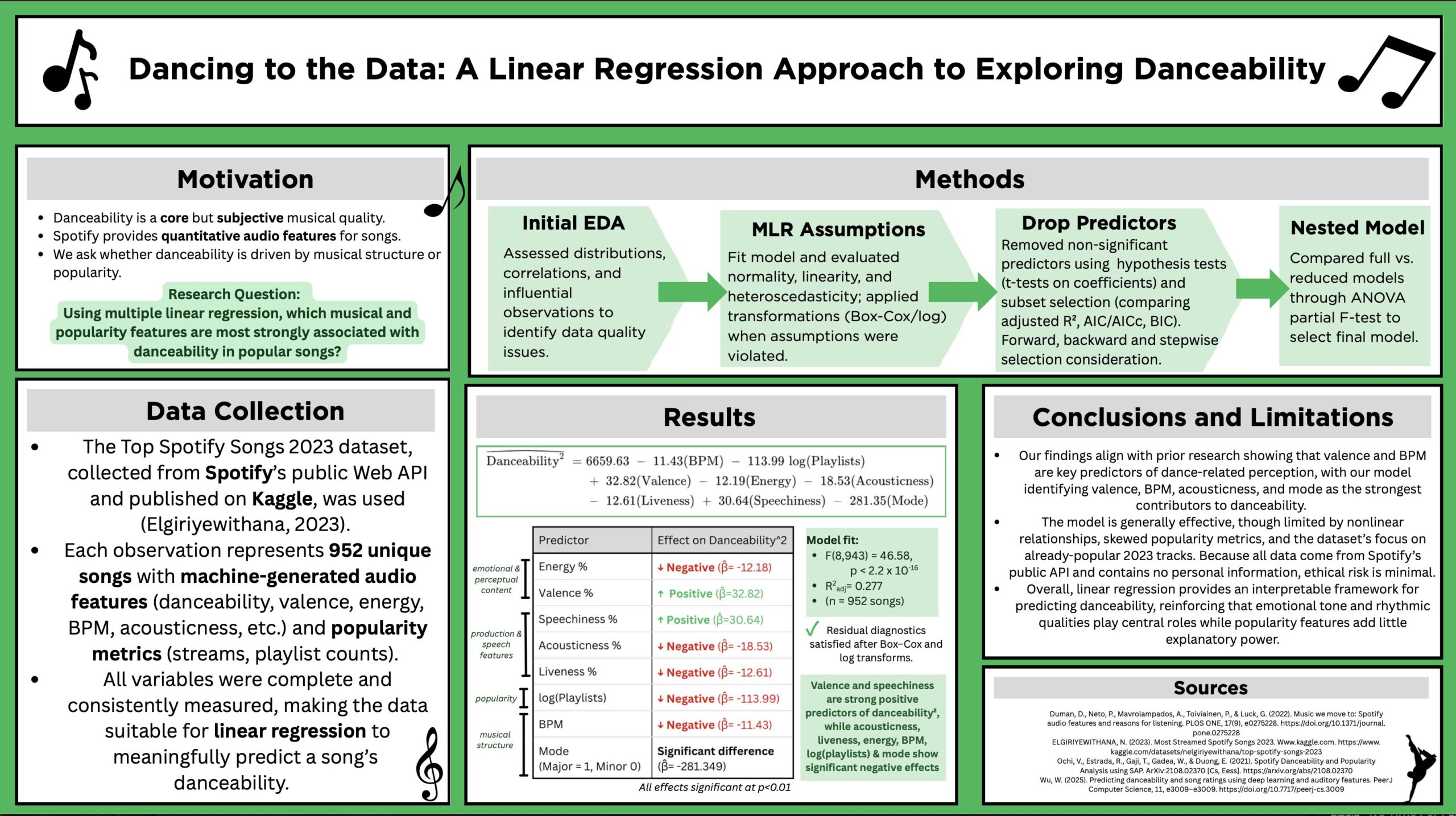

The final model demonstrated strong overall significance:

- F(8, 943) = 46.58, p < 2.2 × 10⁻¹⁶

- Adjusted R² = 0.277

- All retained predictors were significant at p < 0.01

Key Findings

- Valence and speechiness were strong positive predictors of danceability

- Acousticness, liveness, energy, BPM, mode, and log(playlists) showed significant negative associations

- Popularity metrics contributed relatively little explanatory power compared to musical and emotional features

These results suggest that emotional tone and rhythmic qualities play a central role in how danceable a song feels.

Here’s our poster summarizing our findings:

Conclusions and Limitations

This STA302 project demonstrates how linear regression provides an interpretable framework for understanding complex, subjective outcomes like musical danceability. The findings align with prior research, reinforcing the importance of valence and rhythm-related features.

However, the model has limitations:

- Potential nonlinear relationships not fully captured by linear regression

- Skewed popularity metrics

- A dataset limited to already-popular 2023 tracks

Despite these constraints, the analysis shows that musical structure and emotional content matter more than raw popularity when predicting danceability.

Final Thoughts

This project highlights the power of classical statistical methods in modern data science contexts. By combining Spotify’s rich audio features with rigorous modelling techniques learned in STA302 at the University of Toronto, it’s possible to gain meaningful insights into how we experience music—and why some songs make us want to dance.

How Math Assignments Are Really Graded (From a TA’s Perspective) - AshDoesMath

March 3, 2026 @ 1:22 am

[…] And if you’re interested in how structured thinking applies beyond the classroom, you might also enjoy my project analyzing Spotify data using regression on this site. […]